The EU economy is linked to millions of workers worldwide through global supply chains. This imposes both a responsibility and an opportunity for EU companies to positively impact workers’ rights and environmental standards. In early 2023, Germany took a step towards responsible supply chains with the new Act on Supply Chain Due Diligence (Lieferkettensorgfaltspflichtengesetz “), as covered in our earlier post.

Tomorrow, (Friday, 9 February 2024) the EU Member States will vote in the COREPER whether to adopt the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (“CSDDD”), aiming to harmonize companies’ due diligence obligations regarding human rights and environmental matters throughout the EU.

The CSDDD has been provisionally agreed on on a political basis in December 2023. Now the final text of CSDDD must be formally adopted by the European Parliament and the Council of Ministers before it will enter into force. Once ratified, EU member states will have two years to transpose the directive into their domestic law. In Germany, this will likely necessitate modifications and expansions to the LkSG.

The CSDDD, when compared to Germany’s LkSG, introduces further requirements, which we will explore in this blog post. Key distinction in the final agreement of the CSDD include:

- Broadening the scope of affected entities.

- Extension of the covered supply chain.

- Enhanced liability paired with stricter sanctions.

- Further focus on climate considerations.

Delineating the Changes Between CSDDD and LkSG

Scope Expansion Under CSDDD

Many more businesses will be covered by the CSDDD than by the German LkSG. The CSDDD encompasses both EU-based companies and companies from third countries, provided certain thresholds of employees and turnover are met.

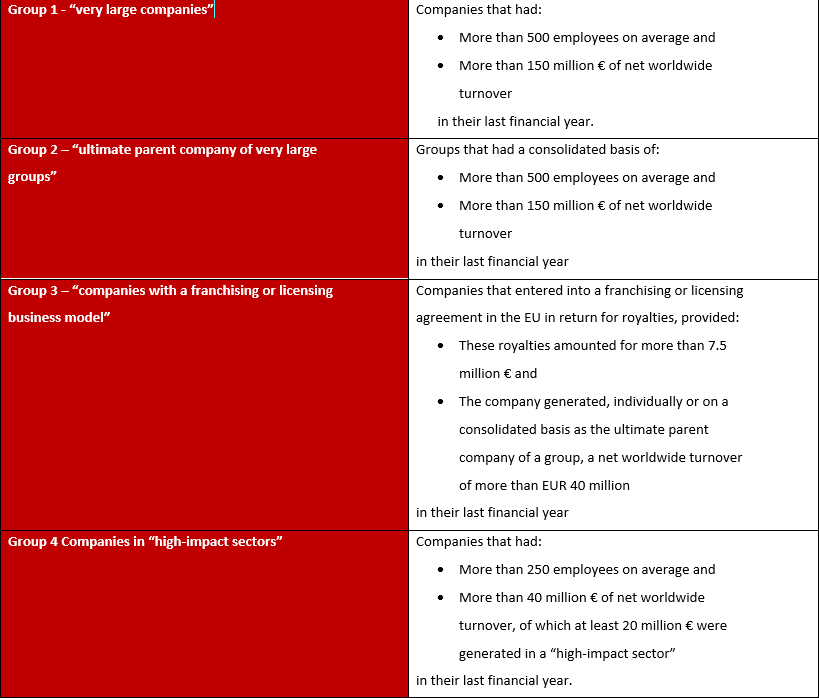

For companies constituted under the laws of EU member states, the directive applies if the company falls under one of the following Groups:

In contrast, the German LkSG has no turnover threshold and has applied to companies with at least 3,000 employees in 2023 and applies to companies with at least 1,000 employees since 1 January 2024..

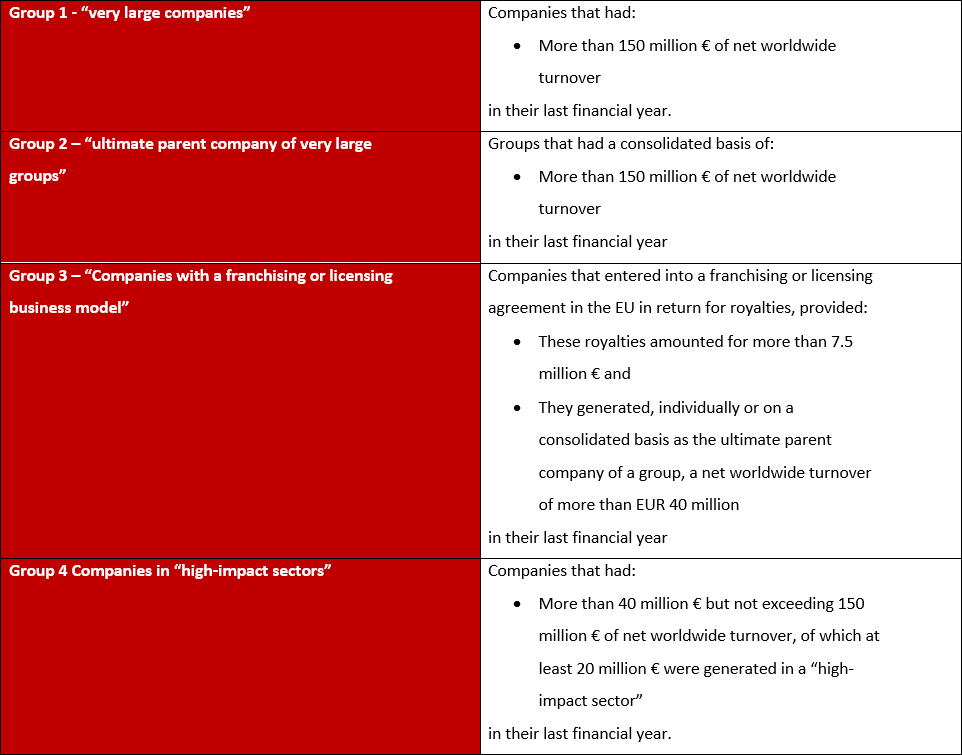

Both the LkSG and CSDDD address non-EU companies. The LkSG applies to non-EU companies with a German branch employing at least 1,000 employees. In contrast, the CSDDD targets companies even without an EU presence, provided they meet the relevant turnover thresholds within the EU:

From Supply Chain to Comprehensive Value Chain

Also in its scope of examination, the CSDDD goes beyond the LkSG. The term supply chain as defined in the LkSG is limited to due diligence measures within the company’s own business area and its suppliers. However, the CSDDD broadens this scope to the chain of activities. This means due diligence requirements will cover a company’s own business activities, as well as those of its subsidiaries, extending to both the upstream and certain downstream sections of the chain of activities.

- The upstream chain of activities includes all activities of a company related to product manufacturing, such as raw material extraction, and provision of services.

- The downstream chain of activities includes activities conducted by business partners regarding distribution, transportation, storage, and disposal but excludes disposal of products by consumers. The distribution, storage and disposal of products subject to export controls are also excluded.

New Liability Risks and Stricter Sanctions

A glaring divergence between the two legislations arises in civil liability. While the LkSG explicitly excludes civil liability, it is included in the CSDDD. The idea behind it: ensuring an even more effective enforcement of due diligence obligations. The CSDDD enables affected parties to directly file claims against companies for damages stemming from intentional or negligent violations of obligations under the CSDDD. A company cannot be held liable if the damage was caused solely by its business partners in the chain of activities.

Sanctions in case of violations of due diligence obligations have already been the case under the LkSG in Germany. However, with the CSDDD, these penalties extend further. They may include fines of up to 5% of the annual group turnover and public disclosure of the violation naming the company (“naming and shaming”).

An Intensified Climate Mandate

Both law texts aim to protect human rights and the environment. Yet, the CSDDD adopts a more holistic approach with regard to climate protection due diligence. It requires all companies, except those of Group 4, to adopt and put into effect a transition plan aligning their business strategies with sustainability and limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (Paris Climate Agreement). The CSDDD further obliges these companies to align their transition plan with the EU’s goal of climate neutrality by 2050 and a 55% emission reduction by 2030. Notably, such requirements are absent in the LkSG.

Management’s Role

The role of company management is absent in the final agreement of the CSDDD. While earlier versions included personal and direct liability for putting in place and overseeing due diligence obligations as well as variable compensation tied to meeting certain goals, these were all cut from the final agreement.

Practical Takeaway

As we await the European overhaul, Germany’s LkSG has been in force since the beginning of 2023. The LkSG serves as a valuable practice to prepare for the new CSDDD. Companies already compliant with the LkSG’s provisions are well on their way to tackle the CSDDD’s new challenges.

For companies potentially falling within the scope of the new CSDDD, we recommend the following check list to assess alignment with the most important LkSG requirements and readiness for the CSDDD:

- Has your company established a risk management system that allows for regular risk analyses within the company’s own business area and among its suppliers? With the new CSDDD, risk analysis becomes even more important, serving as the linchpin of supply chain due diligence.

- Has your company designated a Human Rights Officer or an equivalent to oversee risk management? Are these individuals adequately trained?

- Does your company have an internal complaint procedure for disclosing human rights and environment- related risks and violations?

- Has your company issued a policy statement addressing its strategy on human rights and environmental matters?

Time to Make a Move

While the CSDDD and LkSG share foundational similarities, the former introduces noteworthy alterations and tightened standards. These changes span from broadened applicability to comprehensive due diligence obligations, and the introduction of civil liability and heightened environmental obligations. For companies, this shift is a call to action, drawing on lessons already learned from LkSG compliance. With the adoption of the CSDDD on the horizon, Baker McKenzie is here to help. As experts in the field of ESG, compliance and investigations, we are committed to guiding clients through the evolving landscape of corporate accountability in supply chain management.